I met Giorgia Pavlidou, surrealist poet and painter, through FB, the day before she moved from Los Angeles to Greece. We’ve been published in Clockwise Cat (curated by Alison Ross), and it’s been my privilege to publish both her words and artwork in Al-Khemia Poetica.

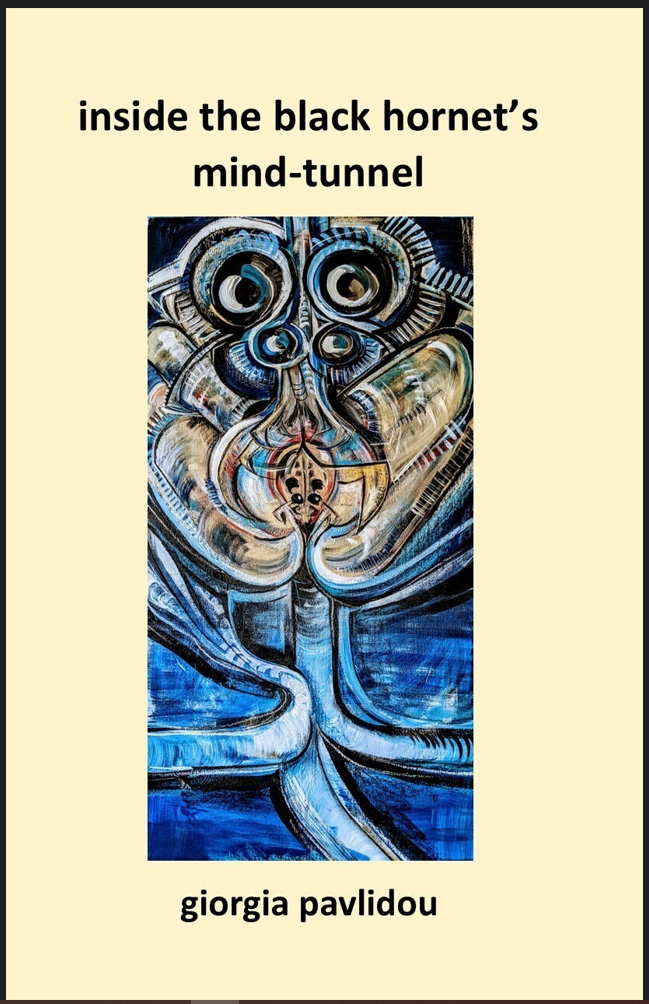

Her chapbook, inside the black hornet’s mind tunnel ( © 2021 Trainwreck Press), is the perfect fusion of surrealist poetry through a shamanic lens. Pavildou graciously agreed to an interview, and what she has to say is not only worth reading, but also remembering.

AKP: What circumstances led to the creation of your new chapbook inside the black hornet’s mind tunnel?

GS: I either observed or hallucinated a giant black hornet exiting a little tunnel in one of the walls of my home in the Peloponnesian Highlands, in Greece. There are solitary European hornets active in the area. I've seen many, but they aren't black.

The image of the animal, and especially its droning stuck with me. I kept on hearing it while traveling back to LA. The volume of its madlike current apprehended me.

In some awkward way, it appeared protective (of me).

Reading about solitary hornets, I discovered a mercilessly matriarchal world. This experience and subsequent discoveries inspired me to start writing. I typed, typed and typed, & unintentionally the piece acquired incantatory dimensions: the hornet as totem, birthing "manic wasp voltage."

Maybe to navigate the mania of

contemporary urban living?

The hornet's vibrations, like the shaman's drumming, opened me up to a portal leading to some other dimension. Think of it: there're hardly any wild honeybees in cities but beaucoup of wasps. Wasps thrive both in rural and urban environments. They can exist in two worlds: they're amphibians.

I think the tunnel refers to the imagination. To survive life in an overly canned and artificial environment, I need to cultivate and ramp up the faculties of my imagination. The black hornet's droning induces a trance that helps with that.

AKP: How would you define the phrase “living mythically”? Do you see yourself, as a poet and painter, actively involved in this process, and if so/not, why/why not?

GS: Myth probably is the default, and so-called reality is the socially sanctified narrative imposed/painted over it. I think our personal stories have epic qualities. Even the seemingly most boring life has heroes of sorts. Boredom is a powerful antagonist.

As a species, we're constantly redeeming ourselves. Our culture of commodification, however, has turned perfectly natural existential life-events and organic states of consciousness into deficits, and guess what, one can find a semblance of relief in psychotropic medication, quick-fix therapies, tourism, Netflix, fast food, Tinder and so on, which is, abracadabra, to the benefit of bourgeois society and the corporate world.

In this psychological black hole that LA sometimes can be, thinking of the Eurydice and Orpheus myth helped me understand my mission, the dangers, and possible rewards of my Californian meanderings.

I have encountered many Calypsos who, like Odysseus' Calypso, tried to distract me. Practicing divination can help with distinguishing the path from the detour. Poetry, perhaps, is a form of divination. It opens up the practitioner to a near-endless world of meaning and imagining.

One feels stuck when the quotidian colonizes the mythological. In Western societies, the life-world

is emptied out of all myth and understood only in terms of use value.

In my experience, the forest I live close to here in Greece is alive. It's a brain, a mind, a brainforest - not just wood. I feel it has incorporated me, as if I'm a family member. The trees are my family. I feel uncomfortable when I need to leave it for a while, and constantly think of it when I am away. This green mind feeds me. This is the myth I dwell in. Though I'm a clinical psychotherapist by training and profession, (though not by vocation. By vocation I'm a writer and painter), I refuse to understand

my life and other people's lives in clinical or psycho-medical terms. I find that one-sided and reductionist. I prefer thick descriptions. Myth is thicker than psychology.

AKP: Your title poem contains Sanskrit and Greek names/descriptive, which you very thoughtfully provided a guide for the reader to navigate. You chose words that contain multiple meanings. What was the inspiration for this, and why/why not do you think this will add to the reader’s experience?

GS: Some readers might feel irritated. Others may feel that it's presumptuous. A group of readers, however, are susceptible, I think, to the hypnosis of seeing another script and experiencing an archaic language. These words can create a wonderful exhaust and exit, especially for English speakers. The English language is so dominant, it locks you up in a one-only world-view. See these archaic foreign terms as tiny alchemical escape-hatches or windows, roads towards syncretism and multiplicity, as medicine and antidote to microwavable forms of speech disguised as language.

Poetry is a lifebuoy for the mind, used by those who understand that their nervous system is flooded with stereotypes.

Maybe even the irritation of seeing another script and feeling it's presumptuous, is enough to help you snap out of the hypnosis of the taken-for-grantedness of your own life. The script exoticizes the domestic. This alien element breaks the habitual, the mechanical, and hopefully creates some space to adopt a more

lyrical approach to living, reading and writing.

AKP: Kali Ma is not only regarded as a destructive/creative goddess, but also, as a harbinger of the time we now live in (Kali puja). What led you to associate the Kali experience with that of being inside a black hornet’s mind tunnel?

GS: Women have traditionally been understood in western cultures as weak, so is the feminine.

When we look at the animal world, however, we see that the female world is merciless. Perhaps it's a bit hyperbolic, but I enjoy seeing a touch of mercilessness in a woman, even if it's only imagined and not practiced in physical reality. Kali in Sanskrit, freely translated, means the Black lady. But Kaala in Sanskrit also means time. Mahaakaal is the God of death, because basically it's Time that'll maim us all

in the end. Kaali is also protective.The solitary hornet will literally do everything and anything

to raise her larvae. Kali protects her offspring from the excess of the extroverted forces of masculinity, of

lineair time. The world of Black insects is radically female and its totally mercilessness. This is

probably why something in me associated being inside the Hornet's tunnel with the protective virtues of Kali, the all-protecting but also all-devouring ancient Mother. Inside the Hornet's tunnel Kali's kids are hibernating. The hornet will sedate its prey and transport it to her young so that they feed from fresh meat. Isn't this Love with a capital L?

AKP: You cite the poet Will Alexander as one of your influences. How has his work influenced yours?

GS: Without WA I probably wouldn't be writing poetry. WA doesn't practice linguistic acrobatics or muses over faits divers. WA's practice is applied linguistic alchemy or sonic shamanism, glossolalia of the first order, Jazz. This poetic tradition goes back to ancient times where poets were druids, oracles and other medicine people. Yet this bebopping isn't as random as it seems. It's fueled with acute observations of the mind of our times.

My meetings with WA, reading and researching his work has helped me move away from cognitive understandings of poetic practice, like when you start with a rather well defined idea and apply an accepted meter or form to develop it further. I find that boring.

I begin writing, and write, and write, and write. This is the prima materia, the magna confusa.

Gradually images, shapes, characters, storylines, cadences, musings and music will emerge. Then I keep on kneading, kneading, kneading. I read out loud. The words reverberate physically in my throat. A rather tangible brew is massaged into existence. Without WA I'd probably still be struggling with how-to books instead of trusting my neurology to bebop on the page whatever needs to find form and expression.

AKP: As a poet and painter, how do your two mediums enhance the other?

GS: The visual strengthens the verbal, it's like cement. The linguistic comes first, though. The image is dangerous, it's therapeutic as well as poisonous, but it can also serve as an inspiration. Write poems as if you're painting on a canvas, painting with words, writing with pigments, and vice versa.

AKP: Your poem “Suicide Chez Jeff”, explores the idea of suicide as a commercial product, specifically sold through L’Amazone (I see what you did there). What are your thoughts on the legality of suicide, and the right to choose to choose to end one’s life on their own terms?

GS: I grew up in Northwestern Europe. Euthanasia is a total non-issue there. I find it strange that it doesn't exist in California or elsewhere. Turning it into a commercial product would take commodification to another level. I tried exploring that cynical reality in Suicide Chez Jeff. Perhaps in some future point you can apply for euthanasia online. What would that look like? When will that become a reality?

AKP: What’s your next project, and when will it be released?

GS: I just finished two new manuscripts: "Female Body Retold," and "Appetite for Abjection." I have submitted these to a few small scale avant-garde presses. It'd mean the world to me if you'd keep your fingers crossed with me.

© 2023 marie c lecrivain